Thoughts On Front End Architecture

Early in September I decided that I was going to rebuild the front end of my new product. Part of why I made this decision was because I had built my alpha with the intention of rebuilding it. A lot of that decision was because of what I wanted to do with my content pages.

I personally dislike most home and content pages. They have a lot of content, but end up saying very little about what the product actually does. I dreaded the thought of creating that kind of content.

Then I noticed that nearly every rich text editor has on their home page… a demo of their rich text editor. How perfect! Instead of a lot of rambling, they just show you the product up front. You can tell immediately whether you like it or not. No need to skim past a lot of marketing speak.

The problem with trying to imitate this is that RTEs demo really well because the product is a pure front end component. Being able to display it easily on any web page is table stakes. My product has a backend to deal with. Allowing a public facing demo to affect your backend has all sorts of issues involved and requires a lot of custom development just for the demo.

So the goal for me was to rebuild my front end in a way that would allow me to reuse the production front end code and use demo data instead of an actual backend. Another important point here is that the full application does not fit nicely into a component on a web page:

This means I needed to be able to extract a single component from the app and have it be completely functional:

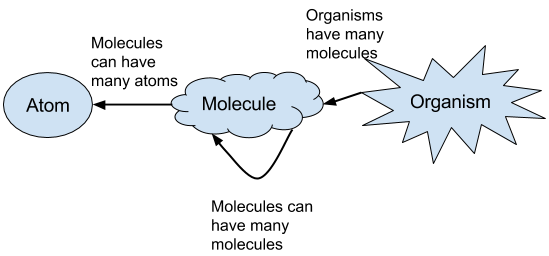

I took on some heavy influences from atomic design and Flux for this. Atomic design in a nutshell is applying object oriented principles to front end components. The smallest component in a frontend is an atom. These are literally buttons, input fields, text fields, etc. Next up are molecules that contain multiple atoms. Organisms contain molecules. Templates contain organisms. Pages contain templates.

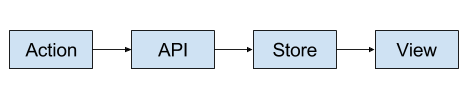

Flux is essentially the idea that data flows one way. Your view contains your buttons, text fields, and images. A button doesn’t actually affect the View. It triggers an Action which manipulates the data in a Store. The Store then tells the View what to display.

The part of Flux that’s left to developers to decide on is how to implement API calls to a backend. This is the part that affects me the most given my goal of having a back end free demo. The naive solution is to create a new class for API calls and stick it in between actions and the store.

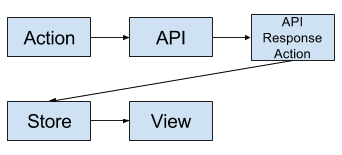

But how do API responses get handled? Inside the API class? To have a backend free demo, I would also need to separate the code that calls the backend from the code that processes the data. The solution here is a different type of action that isn’t triggered by the UI, but triggered by a response from the API call.

But how do API responses get handled? Inside the API class? To have a backend free demo, I would also need to separate the code that calls the backend from the code that processes the data. The solution here is a different type of action that isn’t triggered by the UI, but triggered by a response from the API call.

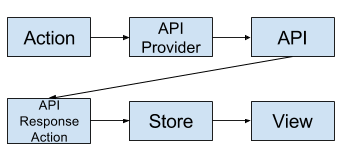

I’ll also need to have another class that is used to determine what implementation of API I want. This way I can swap out a Demo API with the Server API seamlessly.

I’ll also need to have another class that is used to determine what implementation of API I want. This way I can swap out a Demo API with the Server API seamlessly.

So where does atomic design come into play?

So where does atomic design come into play?

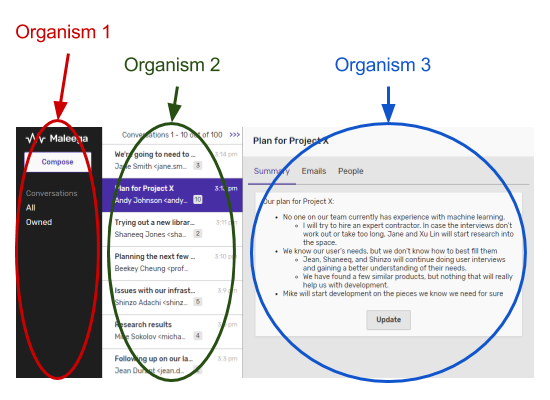

Somehow the store is supposed to tell the view what to display. But the view is made of lots of components. Which one should the the store talk to? For my application, I know that there are certain components that I would like to be standalone applications. These would make my demos.

I judged these components to be my organisms. For me, an organism is something that can be completely self sufficient and does not need the context of other organisms.

With that at the top level and atoms at the bottom level, we’re left with molecules. Given how complex some of my screens were, I needed more than just 3 levels of components. That means molecules can contain other molecules as well as one or more atoms.

Meanwhile, the store will only ever communicate with an organism. It is the organism’s responsibility to pass down any data to its molecules.

Now if I need a production app, it contains code for the Server API and all 3 organisms.

If I want a demo app, it contains code for a Demo API and one organism.

The amount of code for a demo app is < 50 lines + some JSON data for the content. Oh and almost all of the demo app’s code is boiler plate stuff like function signatures and import statements. The time it takes to build a demo app is less than 5 minutes (not including content).

This architecture has some other advantages too. I’m a primarily back end developer and have torn out a lot of hairs debugging front end code in the past. With a clear separation of responsibilities (e.g. only actions can initiate changes, organisms are the bridge between the store and all other components), it becomes much easier to find out where bugs are. Finding root causes with front end bugs rarely takes me more than a few minutes now.

On top of that, the ability to build out a demo app means I can also build out a test app. The problem I always encounter with building selenium testing frameworks is how to make sure every test has a deterministic data set. That’s really challenging with a backend that changes state every time a test is executed. With this, I can just create a “Test API” that’ll get reset before every test is run. No weird infrastructure to restore seed databases or boilerplate test code to set up and reset test cases.

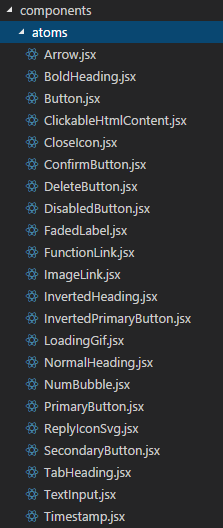

There is a huge downside to this way of building front ends though: a LOT of typing. At least in the beginning. Making sure every piece of the UI can be boiled down to an atom results in a lot of atoms getting written:

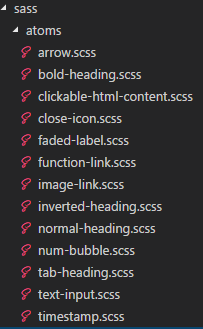

Oh and did I mention that each had its own SASS file for CSS?

I often encountered a situation where I asked myself “Do I really want to type out this field as an atom?” It took a bit of willpower to commit to that pattern.

Having organisms as the bridge between the store and molecules also means that you may end up having to touch a LOT of molecules in order to get access to some data. I found myself modifying half a dozen files just to get one field displayed. An interaction with the server can easily require touching twice that amount of files. That’s a lot of mindless code to write.

In the end, I found this to be a small price to pay. Most of my time usually isn’t spent typing code. The time is usually spent debugging code. A few extra minutes of typing is much more preferable to a few hours of debugging. On top of this I can have a demo app that uses the same code as the production app, which saves me time in writing that code and testing it.

I keep this blog around for posterity, but have since moved on. An explanation can be found here

I still write though and if you'd like to read my more recent work, feel free to subscribe to my substack.